When I set out to write this essay, I wanted to use Hardy’s novel to talk about what’s happening to land around the North Carolina Piedmont. As it happens, the novel turned out to be far more interesting and complicated than I had expected. So, without further ado, here is a reflection on a novel by Thomas Hardy. I try to balance information and analysis so that you have some clue of what I’m writing about. If I don’t totally lose you here, or maybe even if I do, please stay tuned for next week, where we’ll be talking about weeds and whatnot.

“What belongs to me I keep.” Marty South, The Woodlanders

Thomas Hardy’s novel, The Woodlanders [1887], opens with a disturbing encounter. It’s evening, and a young female laborer named Marty South sits on a chair by the fire. Working by candlelight, she chops and carves sticks of hazelwood into spars: long, thin, three-sided rods that will be twisted into a U-shape and put to use in the construction of thatch rooves. With a bill-hook in one hand and a leather glove on the other, she works for hours into the night. In the morning, someone will come and take the spars to Mr. Melbury, the timber merchant, who will pay her eighteen pence per thousand and carry them to market to be resold in a town some miles away.

In a single night, Marty hopes to make about a thousand and a half spars. At her feet lie immense piles of wood chips and bits of refuse. She is highly skilled at her work. Later, another villager will look at her spars and remark that they belong in furniture, not thatch rooves. But Hardy tells us that she is a worker who must “[turn] her hand to anything” (58). As a poor laborer, Hardy writes, “[Marty] had but little pretension to beauty”; “the necessity of taking thought at a too early period of life had forced the provisional curves of her childhood’s face to a premature finality.” And yet she lays claim to one particular glory: her hair, whose “abundance made it almost unmanageable,” and whose color, by careful study, “would have revealed that its true shade was a rare and beautiful approximation to chestnut” (10).

Marty’s solitude is interrupted by the arrival of a man named Mr. Percomb. Percomb is the village barber, and he stands at the threshold of her cottage, watching through the cracked door. His eyes are drawn to Marty’s hair. At first, she doesn’t see him. Hardy tells us that his hands finger an object in his coat pocket. Eventually, he steps inside the open door and addresses her: will she, Marty, agree to sell her hair to him? He must have an answer soon. “The lady that wants it wants it badly,” the barber proclaims. “She’s been hankering for it,” he says, ever since the previous Sunday when Marty sat down in front of her in church (12). The lady intends to go abroad as soon as possible, and so she must have it as soon as possible. Marty guesses the lady’s identity: Mrs. Charmond, the former actress, heiress, and landowner who controls nearly all of the woodland and cottages that make up the village of Little Hintock and its environs. Marty refuses; Charmond will never have her hair. Weighing the matter over, Mr. Percomb pulls out two gold sovereigns–roughly thirty times what Marty will make in a single night–and places the coins on the mantle. Think it over, he says, and choose wisely: “you see, Marty, as you are in the same parish, and in one of this lady’s cottages, and your father is ill, and wouldn’t like to turn out, it would be well to oblige her” (13). Marty has until tomorrow to decide what to do. Percomb departs, and Marty gazes into the mirror, where “the two sovereigns confronted her from the looking-glass in such a manner as to suggest a pair of jaundiced eyes on the watch for an opportunity.” (15).

Thomas Hardy, in all his mustachioed glory.

As you might expect (and all the more so, if you’ve read any of Thomas Hardy’s novels before), Marty’s resistance to Percomb’s proposal erodes rather quickly. When Percomb first approaches her, she is tempted a little. But when morning comes, she learns that two other villagers in Little Hintock are engaged to marry: Grace Melbury and Giles Winterbourne. Grace is the daughter of the merchant who acts as Charmond’s business agent; Giles is a yeoman farmer who happens to hold the lease on the cottage that Marty and her sick father live in. It just so happens that Marty is secretly in love with him. By the time that Grace returns to the village, Marty’s romantic (and financial) hopes will be dashed. With a pair of shears, she tears the locks out of her head and places them lengthwise over the top of the same stool she worked at the previous night. The locks stretch out “like waving and ropy weeds over the washed white bed of a stream” (19).

As the novel marches on, the character of Marty South recedes to the background of The Woodlanders. She appears now and again, and the memory of her story will occasionally rekindle in the reader’s mind. However, as I read the novel for the first time a few weeks ago, I found that she cast a surprisingly long shadow over the rest of the book. As if written in shorthand, the story of Marty’s hair encompasses every fault line of class, gender, and social standing that will emerge in the village of Little Hintock. We hear of the wealthy and mostly absentee landowning class; a prosperous middleman-merchant; a small farmer; and a handful of landless laborers. Here too is the ubiquity of money, which dominates the interactions of the villagers and the language they use to interpret the world around them. Here, too, is the poverty of the rural laboring class, and the hungry, all encompassing gaze of the landowner who resides, except for the rare occasion, in London or abroad on the continent. At the center of all this, twenty pages in, is a young woman’s painful decision to cut off her own hair to make up what her father cannot earn, thereby ruining her chance of wooing her lover–or so her reasoning goes.

The shadow that Marty casts over the rest of the book has to do in part with the economy of Hardy’s style. His novels tend to be long, but the man knows how to cover ground when he wants to. By my reckoning, in The Woodlanders, only three characters make their appearances outside of the first twenty pages of the book. Maybe this isn’t surprising for a novel set in a rural village that contains twenty cottages (“before a single bird had untucked his head…twenty lights were struck in as many bedrooms, twenty pairs of shutters opened, and twenty pairs of eyes stretched to the sky to forecast the weather for the day,” (22)). Still, it’s not just that the story of Marty’s hair helps Hardy perform a feat of novelistic thrift.

The story of Marty is an example of what Hardy, writing in his journal in April 1878, would lay out as the scheme of a modern “tragedy”: a “gradual closing in of a situation that comes of ordinary human passions, prejudices, and ambitions,” or a narrowing of existential possibility that is experienced by characters as a “relentless progression” (Life and Work, 123). Most critical introductions to Hardy reference this definition to illustrate the novelist’s approach to his rural subjects. But Hardy’s formula, jotted down between a travel log and a note about the superiority of the “letter system” of novel writing, is compelling for what it leaves out: the “closing in” of a character’s future takes place within the context of an already impoverished rural community. Most of his novels are set in Wessex, a fictional place that is supposed to be located to the south and west of London. Historically, this area is one of the most intensively farmed places in all of England. It also belongs to a region where, beginning in the 18th century, a recognizably capitalistic system of labor first emerged between landowners, farmers, and laborers.

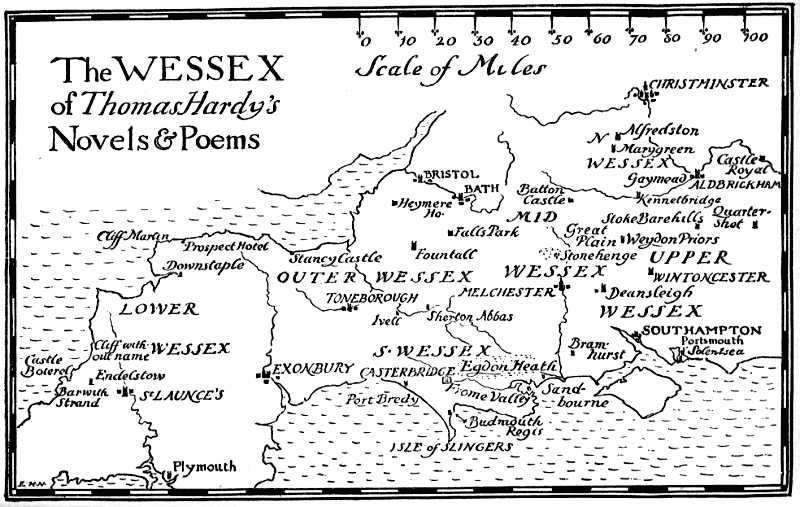

A map of Hardy’s Wessex, which is very much unlike the historical Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex. Like most rural towns, Little Hintock is too small to make the cut. But look for Casterbridge, and when you find it, you’re close.

In the Woodlanders, the story of Grace and Giles’s doomed romance unfolds within the meticulously imagined forests of Little Hintock, a small village that lies north of the fictional Casterbridge (think The Mayor of Casterbridge, another of Hardy’s excellent novels) and the southern coast of England. (Click on the map, if you’re interested.) For years, Grace’s father, the merchant and middleman-agent for Charmond, has paid to have Grace educated in the city. His hope is that through marriage she might lift the family’s social standing beyond what it historically has been: yeoman farmer, or peasantry. The problem is that, before Grace went off to school, Mr. Melbury promised Grace to Giles Winterborne, a woodsman and a farmer who owns leases to several cottages in Little Hintock, including both the cottage that he lives in and the cottage of Marty and her sick father. The type of lease that Giles holds is called a life-lease, which grants him income from the property until Marty’s father dies. When he does die, Giles’s lease is over and he’s forced to join the ranks of common laborers like Marty. At her father’s prompting, Grace chooses to marry Dr. Fitzpiers, the disgraced-nobleman-turned-village doctor, with whom she is deeply unhappy. This, in basic outline, is the plot of the novel.

The landscape around Little Hintock is dominated by plantations of trees that the laborers in the village plant, manage, fell, and ship off to different markets across the region. Among these markets is a harbor on the Dorset coast that Mr. Melbury owns a significant share in (80). Trees cover every inch of the property in and around Hintock. Charmond controls all of it. “Tis timber,” Giles will say; “they never fell a stick about here without its being marked first, either by her or the agent” (93). It’s clearly been a long time since laborers had access to much land. Once, the reader comes across an auction where the villagers are permitted to purchase bundles of firewood or odd-looking saplings that may be turned into walking sticks (49-50). The rest of the timber is bound for distant lands.

A significant portion of the woodland appears to be planted in fir trees. At one point in the novel, Giles is awoken from a romantic reverie and recalls belatedly that he had been contracted to plant a thousand fir trees that day (58). This little detail is a key to interpreting the type of a world the villagers inhabit. Firs aren’t native to Great Britain. The Douglas and Noble fir, which are native to western North America, were first shipped to Great Britain by enterprising botanists in the 1820’s and ‘30’s. In England’s wet, balmy climate (compared to the American Northwest, anyway, where the trees hail from), firs grow fast and healthy. Giles’s trees would almost certainly have been planted and sold for shipbuilding. The old, ancient forest of Hintock is a distant memory. The lone exception is a small network of ancient apple orchards that fleck the hills and vales outside the village. It is in these mixed forests that all the characters, with the exception of the village doctor and the barber, must find a way to earn their living–either in the employment of Charmond or her agent, Mr. Melbury, Grace’s father.

*** *** ***

What is the relationship between the tragedy of an individual human life and the tragedy of a place, of a particular piece of land or a region? It seems to me that, above all, this is the question that animates Hardy’s study of the woodland village of Little Hintock. It is also a question that has preoccupied me, too, as I watch the landscape around me and the people who have inhabited it for generations transform with amazing speed. Land prices soar; stands of pines and hardwoods (cash crops, of course) are clear cut for suburbs and large developments; great masses of earth pushed around for roads, highways, parking lots, and apartment complexes; the mass incursion of new energy infrastructure, both renewable and fossil fuel–all of this happening within ten or so miles of our farm, and dozens (hundreds?) of other places around the Triangle and Triad region.

In my case and in Hardy’s, it’s relatively easy to name the economic and demographic pressures that are causing this transformation. It’s much more challenging to understand what effect these pressures have on the individual lives of rural people. Some of them will no doubt make money off of land that remains in their family. But what about those that have no property to speak of?

Think again of Marty: she shaves off the “chestnut” locks of her hair; the economy of Little Hintock is dominated by the felling of timber destined for distant markets. Both forms of capital, human and natural, are entwined, and not just because they are coerced by the same person. Hardy’s imagery makes the connection explicit. But what precisely is the mechanism between the exploitation of one and the suffering of the other? How are we supposed to relate, in social or political terms, personal degradation with the broader degradation of a landscape or a region, while at the same time insisting on the dignity of both?

We can get a sense of how tricky this question can be by looking at a conversation that Grace Melbury has with Ms. Charmond, the heiress and landowner, early on in the novel. Charmond is giving her a tour of the manor house of Hintock, which is several miles away from the peasant village where Grace’s parents live. At the very beginning of the tour, Grace’s eyes catch sight of something odd along the walls of the gallery the two women meet in. “Ah; you have noticed those,” Charmond says, explaining to Grace that they are traps designed to catch illegal poachers of timber or game. It turns out that her deceased husband was a “connoisseur in man-traps and spring-guns and such articles” (54). Charmond says that he collected “such articles” from neighbors and before his death could recount each object’s history–“which gin had broken a man’s leg, which gun had killed a man” (54). Grace smiles; she has clearly received the right training. Two generations back, these things were designed to kill and maim her own family. Then she says something remarkable: “they are interesting, no doubt as relics of a barbarous time happily past” (54).

Grace’s comment is not too dissimilar from someone decrying chattel slavery and expressing gratitude for the end “of a barbarous time happily past.” It is true that chattel slavery is an institution “happily past.” But it’s preposterous to pretend like the suffering of black peoples in America is over, or that its legacy has miraculously vanished. On the face of it, Grace’s comment is literally true: man traps were a thing of the past. Woodlanders was published in 1887; by the end of the first quarter of the 19th century, traps that caused lethal harm fell out of use and were finally outlawed in 1827. (In his Rural Rides (1822-26), Cobbett notes a sign on a tree that reads: “spring guns and steel traps are set here.” The estate where he finds the sign is called Paradise Place. Cobbett: “They invariably look upon every labourer as a thief” (164)). It is absurd to suggest that Marty and all the other characters aren’t trapped by “gins” [engines] of a more subtle and sinister kind than spring guns and steel traps.

We might be tempted to say that in Hardy’s thoroughly capitalist Wessex, tragedy, the narrowing of individual possibility, is simply a refraction of broader social and ecological crises that no fictional narrative could ever fully encompass. In The Woodlanders, the ordinary (that’s Hardy’s word) works like a prism through which the flows of capital and money are felt if not fully grasped. As in realist fiction, so in reality: capital, both human and natural, is subject to a network of social and economic forces that even the keenest historian will find bewilderingly complex. It is only in the context of the ordinary and the particular that the contingencies of history may be measured and its multitude of tragedies felt.

With any tragedy, though, there is the problem of recognition (anagnorisis). At no point in this novel does any member of the laboring class express resentment towards their employers. Instead, Grace is embarrassed at the uncouth manners of her father and mother who, although comparatively wealthy, remain excluded from the higher castes of society. When she returns, Giles suddenly appears crusty and rural; it’s not until Fitzpiers becomes bored with her and begins an affair with Charmond that Grace’s attraction to Giles is rekindled. Marty never expresses anger or resentment with Mrs. Charmond or Mr. Percomb; at times she seems flattered by the interest. Only once does Mr. Melbury work up the courage to confront Charmond about her affair with Fitzpiers. But the most painful failure of recognition (to this reader, anyway) is with Giles.

When Giles loses the lease to the cottages he has lived in and managed since he was a boy, he feels resentment not towards Charmond but to his own family: his yeoman father, of course, but also his ancestors. The type of lease that Giles owns is called a lifelease, which grants him income from the cottages that he, Marty, and Marty’s father occupy. A lifelease grants the owner income from property for the lifetime of an individual specified in the lease. This individual happens to be Marty’s sick and deranged father, who is convinced that the tree outside his upstairs window will uproot and flatten his cottage. When Giles cuts down the tree for him hoping that he will improve, he dies the next day from shock.

As Giles looks over the lease, which is now expired and has reduced his income by a half, he wonders why his father never took out an insurance policy on it. And he wonders, too, why his ancestors ever agreed to exchange the copyhold they once held for a lifelease in the first place (90). In a copyhold, a peasant was granted certain rights to property in perpetuity. As one historian puts it, by the eighteenth century, “tenure by copyhold became merely a form of landownership, without any servile taint” (Holdsworth, An Historical Introduction to the Land Law (Oxford, 1927), 44. Giles will write to Charmond, who is abroad, and plead his case. But when her lawyer responds, he informs Giles that Charmond “sees no reason for disturbing the natural course of things” (97). Giles’s cottages will be torn down and the land planted in more timber.

Unlike Giles, we don’t have to wonder why his family gave up the copyhold. There are only two possibilities: bribery or violence. It is not a small irony that, when Charmond returns to Hintock for a visit, her carriage accidentally strikes the rubble that was once Giles’s cottage and is overturned. She didn’t even know where his cottage was, not when it was still intact or when it had been torn down. Does Giles laugh with the reader? Does anyone? As the novel lurches to its mawkish, elegaic conclusion, the answer isn’t clear.

*** *** ***

In the Preface to Lyrical Ballads [1800], William Wordsworth explains that “humble and rustic life” is worthy of serious literary treatment ”because, in that condition, the essential passions of the heart find a better soil in which they can attain their maturity, are less under restraint, and speak a plainer and more emphatic language… and…because in that condition the passions of men are incorporated with the beautiful and permanent forms of nature.” It seems to me that, judging by the great bulk of his prose output (it is great in both senses; these books are long and mostly excellent; I think of Henry' James’s “big baggy monsters” descriptor), Hardy absorbed Wordsworth’s intuitions about rural settings and characters, even if those intuitions were less radical than they were in Wordsworth’s time. Hardy alludes to Wordsworth frequently in the novels, and when later in the life Hardy reinvents himself as a poet, the debt to Wordsworth is even more obvious. But Hardy’s novels gesture to a crisis that Wordsworth probably could never have anticipated. We might paraphrase this crisis with a question: with what sense can we speak of “the beautiful and permanent forms of nature” incorporating human passion when nature, and the human society that inevitably belongs to it, have both undergone decisive, large-scale, systemic devastation?

In my essay for next month, I’ll take up this question by leaving behind the dreary world of the Victorian novel and turning to the poetry of John Clare, a farmer, laborer, and self-taught poet who remains one of my favorite poets of all time.